In early 2023, its finances wrecked by the Covid pandemic, BNHC closed the doors of its centre in the heart of Brighton and was reborn as the Brighton Natural Health Foundation (bnhf.org). Freed from the burden of maintaining an expensive building, it is now able to focus all its energy on taking transformative body-mind practices out to all parts of the City, especially to areas with limited access to these precious resources.

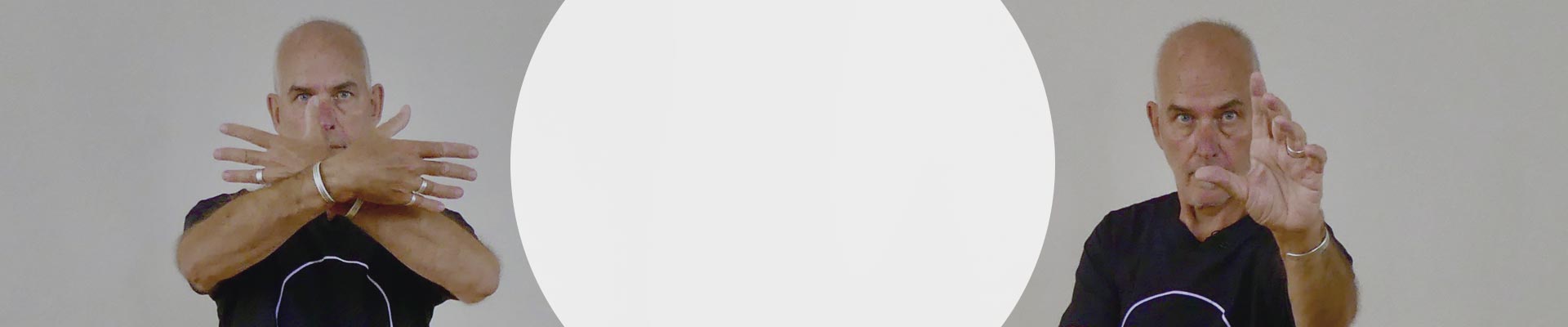

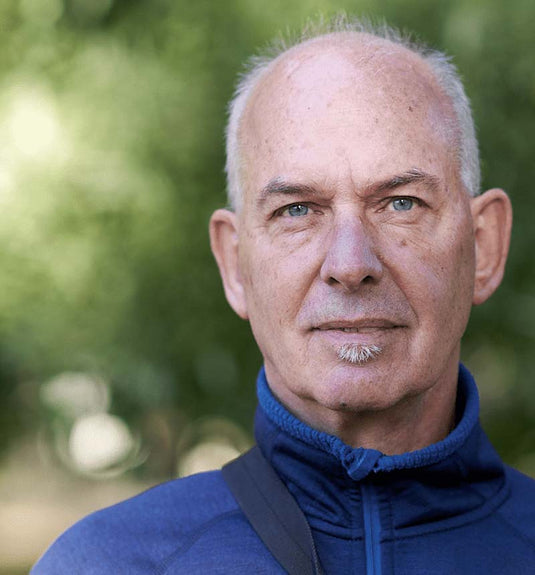

About Peter

After a period of teenage rebellion and restless travelling, Peter co-founded Biting Through – a natural foods restaurant at Sussex University in 1971. This soon led to Infinity Foods – at first a retail shop and then in quick succession a bakery and nationwide warehouse/distribution centre. Infinity Foods is now a large workers co-operative in the heart of Brighton. In 1981 Infinity Foods founded the Brighton Natural Health Centre charity to extend its vision of promoting health in the community through education in practices such as yoga, tai chi, qigong, meditation and other body-mind traditions.

Peter qualified as an acupuncturist in 1978 and as a Chinese medicine herbalist in 1992. In 1979 he founded The Journal of Chinese Medicine – now approaching its 45th year of publication. In 1998 he and his co-authors published A Manual of Acupuncture – the fruit of eight years of dedicated work. Translated into German, French, Dutch, Italian, Polish and Portuguese and available in book, app and website format, it is the number one resource for studying the acupuncture points. In 2016 Peter published Live Well Live Long: Teachings from the Chinese Nourishment of Life Tradition – a book devoted the the art of yangsheng or how to live as long, healthy and satisfying a life as possible. His book Qigong: Cultivating body, breath & mind is due for publication early in 2024.

Peter has lectured globally on Chinese medicine and heath promotion for several decades. He is a committed practitioner and teacher of qigong.

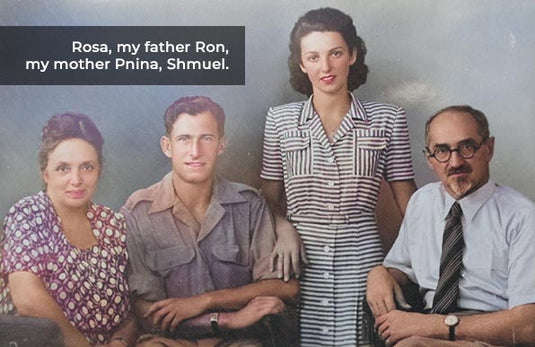

My family

There is a biographical and autobiographical tradition on my mother’s (Jewish-Russian) side of the family.

My grandfather Shmuel Eisenstadt wrote a book about his father and my mother Pnina Deadman compiled a book about her father Shmuel and for good measure wrote her own mini-biography.

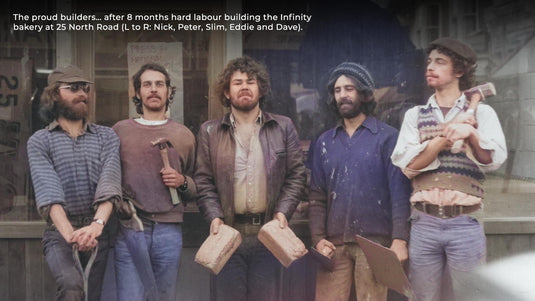

The story of Infinity Foods

The story of Infinity Foods began in 1970 with the setting up of the world’s first macrobiotic student restaurant, Biting Through, at Sussex University.

I had been a student at the University a couple of years before, but it hadn’t worked out for either of us and I did not stay long. I spent as much of the next couple of years as possible travelling and living the hippie life to the full in Moroccan villages in the Ourika valley and outside Essaouira.

The idea of simple natural foods, particularly whole grains and vegetables, was in the air at the time, but in the UK at least, until the setting up of Seed restaurant in London by the Sams brothers, natural eating was dominated by the older vegetarian/naturopathy movement. Basic foodstuffs such as brown rice were only found in tiny and expensive packets in health food shops, otherwise dominated by pills, potions and cosmetics.

New horizons

My travelling life came to an end with a bad case of hepatitis, and it was on my sickbed that I became seriously interested in the macrobiotic approach to health and harmony. Apart from hedonism, this was also the first thing for many years that I felt I could pour all my energy into.

On my return to England I responded to an ad placed by Sussex University student James (then Jim) King in Ceres Grain Shop in the summer of 1970 looking for partners to open a wholefood restaurant at the University of Sussex, and through that met Ian Loeffler who was similarly inspired and also in possession of a small insurance company cheque following a car accident. Thanks to passionate campaigning, the Students’ Union eventually agreed to let us hire a big basement restaurant, and in 1970 we opened Biting Through.

We didn’t know much about cooking – certainly in bulk – but after we’d scrubbed the place clean of accumulated hamburger grease, we started serving brown rice, vegetables, seaweed, unyeasted bread and beans to our undiscriminating customers. Undiscriminating because, blessed with the cast-iron digestions of the young, and with no spare cash, they hoovered up our cheap heavyweight fare by the pot load. As for us, we literally ran for ten hours a day serving up hundreds of meals, assisted by all kinds of volunteers inspired by the idealism (we didn’t believe in profit) and the fun.

Feeding the masses

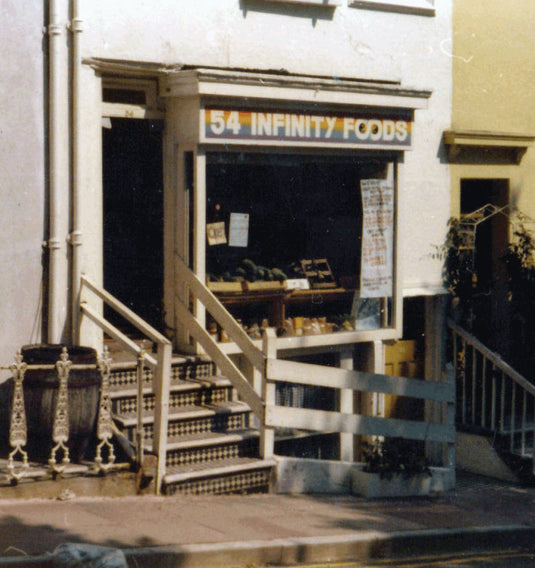

As time went by, we found more and more people knocking at the kitchen door asking to buy rice, wholewheat flour and muesli, and decided to open a shop. Once again lack of money seemed an insurmountable barrier until the day Andy the Anarchist turned up to do his voluntary vegetable chopping looking glum. His problem was an aunt who had died and left him some money. As Andy didn’t believe in private property, our offer to relieve him of it brought a smile back to his face.

But even with this, and loans from various friends and parents, it took a while to find the perfect shop – tiny, hidden away, and very cheap to rent. To start with we had as few as two or three customers a day, and we knew we had to find a way to supplement our microscopic takings. Festival catering was the answer, and starting with the first Glastonbury Festival, and taking in various megarock events on the way, we took our message of cheap, healthy and plentiful food on the road, cooking up vats of lentil soup and rice and turning out meals by the thousand.

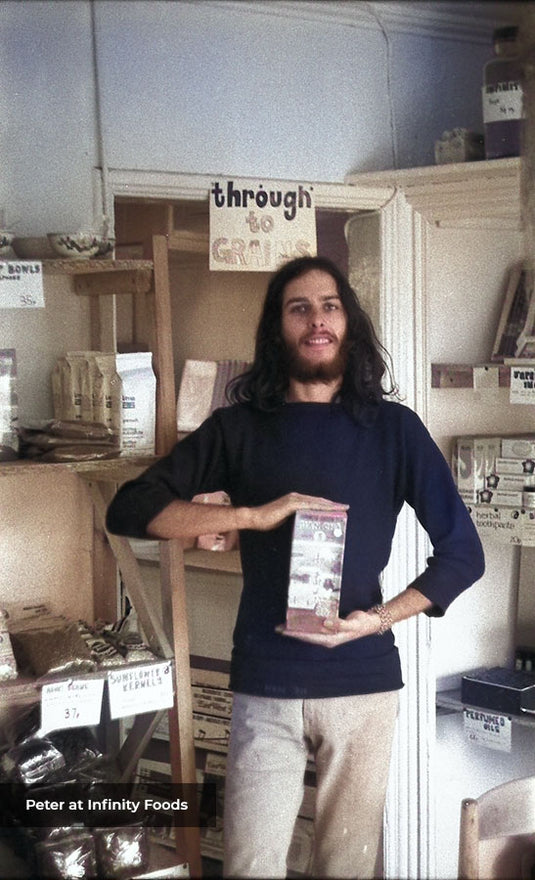

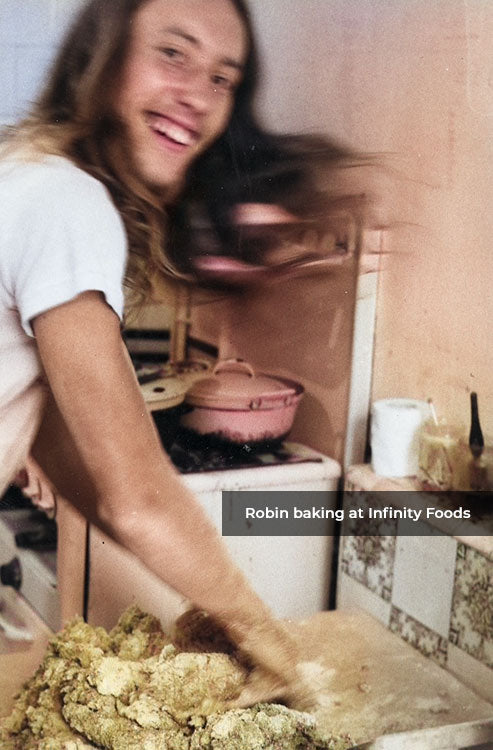

At this time, although many people came and went, a core partnership was formed by myself, Robin Bines and Jenny Deadman, and this partnership lasted until the founding of Infinity Foods Co-Operative in 1979.

Expansion

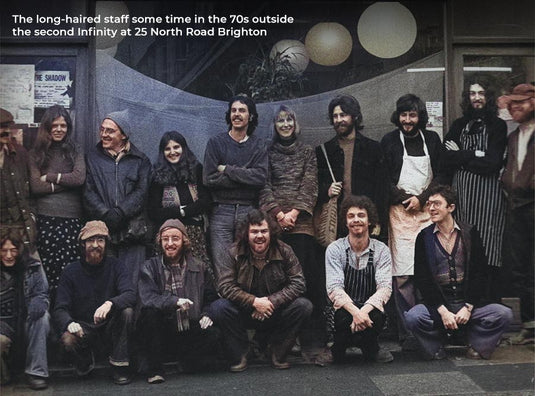

In the years that followed, we moved to a larger shop - http://www.infinityfoods.coop - in a better location (Brighton’s famous North Laines, which I think it’s fair to say Infinity helped transform from a run-down low-rent neighbourhood to an exciting creative and sadly now high-rent neighbourhood). We ran a small market garden to feed the shop with organic vegetables, took on the shop next door and turned it into a bakery, and started a natural foods distribution business. Then, from the ruins of a blaze that burned down the warehouse at the back of the shop, we created The Brighton Natural Health Centre (BNHC). This charity took forward the idea of self-health care beyond diet and started to offer classes in a whole range of disciplines – mainly yoga, dance, tai chi and qigong. The BNHC has recently celebrated its 30th birthday and Infinity its 40th.

Legacy

Infinity Foods ran for many years as a loose informal co-operative, with everyone paid the same wage and decisions made by whoever was most committed at the time. However in 1979 we decided to formalise the co-operative and establish it as a legal entity under Industrial Common Ownership rules, and the three partners gave away the business to the co-op.

Co-Op status principally means that there is minimal differentiation in salaries, that all workers receive an annual dividend, that a percentage of annual profits is committed to charity, and that it can never be sold to the benefit of its workers (if it were sold, all proceeds would have to be donated to a similar co-operative).

Infinity Foods is now a thriving workers co-operative with around 130 members. It is a much-loved feature of Brighton & Hove, helps support a variety of charitable and environmental projects and – through its warehouse arm – distributes natural and organic foods throughout the country.

Brighton Natural Health Foundation

In an expansion of its vision of ‘healthy individuals, healthy communities and a healthy planet’ Infinity Foods founded The Brighton Natural Health Centre (BNHC) educational charity in January 1982. It offered classes in what were fairly uncommon practices at the time such as yoga, tai chi and meditation – alongside dance, Pilates and more. As a charity, it also offered tailored low cost or free classes to different disadvantaged communities.

My Yurt

It must be around 15 years ago that I first went to qigong camp in a damp and windswept field in Devon – on the edge of Dartmoor. I set up my tiny nylon tent and as I lay in it – cold and a bit miserable – I saw a woman draw up in her estate car, laden with poles and canvas. I barely paid attention but when I roused myself an hour or so later I saw this magnificent construction and peeked in the doorway to see her reclining on a pile of sheepskins in front of a roaring wood stove. I decided on the spot that if I ever came back I’d be in one of those.

Over the next couple of years I made two yurts. Two because the first one wasn’t much good – though in my defence the only instructions I had were a few brief and incomplete pages. By the time I made the second, I knew what I was doing.

I coppiced ash poles in Stanmer ParK, close to Sussex University. The woods there – like so many in the UK – were filled with abandoned coppiced trees. Coppicing – that marvellous working relationship between human and tree – once produced long straight poles for numerous purposes (fencing, tool handles, charcoal making etc.) and massively extended the longevity of the tree. I cut poles, stripped the bark, shaved the ends and – what a joy – sat by an outside fire as my homemade steaming box slowly softened the wood, allowing me to bend the roof and wall poles, and wrestle the roof wheel round a steel hoop. Then the poles were drilled, corded and varnished numerous times with fragrant linseed oil and true turpentine. Finally I measured every dimension, sent the numbers off, and a few weeks later received a purpose-sewn canvas covering.

Sitting by the fire in my shangri-la

I confess it’s hard work loading the poles and canvas on top of a car, stuffing the boot with wood stove, chimney, tables, cooking stove and enough bits and pieces to furnish a small house, and then unloading it all and erecting the yurt. But when it’s done – as I think these pictures testify – it’s the source of profound comfort and deep joy.

Bad karma chameleon

"When I was twenty-one, David Bowie (on the cusp of fame) and his girlfriend Mary Finnigan opened the Beckenham Arts Lab in the Three Tuns pub. It was the nearest thing to my local since I’d spent many hours there, mingling with my anarchist and CND friends. And somehow, Mick (guitar), Bob (drums), my brother Alan (harmonica) and I became the Art Club’s house band (going under the dreadful name of Oswald K. Aldehyde). Lacking a trace of self-doubt, we’d launch into blues or jazz covers – Miles Davis’s So What was a favourite – which rapidly degenerated into long and self-indulgent noodlings.

I didn’t take to David Bowie in those early days. Always a chameleon, this particular incarnation was full of a luvvie campness that couldn’t have been further from the worthy authenticity of my black and white politics. As soon as he’d announced us he would disappear into a back room. I had no complaints there – I wouldn’t have stayed to listen to us either – but when he swanned back at the end of our set saying how ‘absolutely faaaabulous’ we were darlings, I choked on the insincerity.

When he died in 2019 I spoke to my brother about those times and he told me something I have no memory of.

“We were at Brian Eno’s house,” he said, “and you had a row with David about how he shouldn’t be charging people money to get into the Arts lab. You kept calling him a ‘bread head, man’ “ [bread head = money-obsessed in hippie talk).

The summer of that Arts Lab year, 1969, Bowie organised Britain’s first Free Festival in our local park. Beckenham Recreation Ground represented everything I’d loathed about growing up in this bland London suburb. Grass cropped to within an inch of its life, dogshit, mean little flower displays, thorny, clipped bushes spaced out along bare and barren beds, a sour and officious park keeper and bored kids hanging out by the swings, smoking, and wondering what terrible fate had condemned them to live in Beckenham. This was the park where I’d walked our dog Rex as a kid, wondering when the hell my life was going to begin.

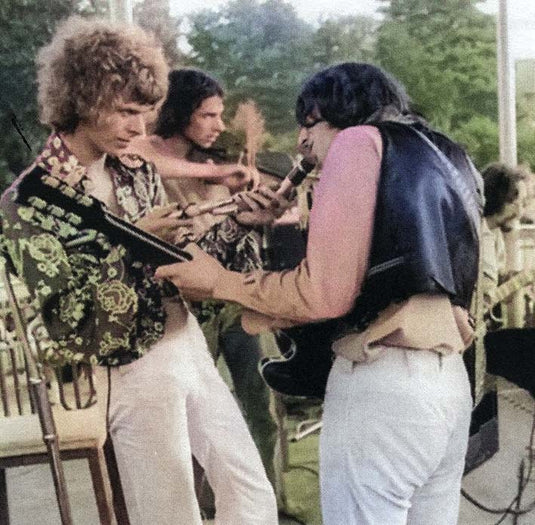

But this day it was transformed. A crowd of hippies lounged on the grass and the smells of weed and patchouli wafted through the park. We’d put together a scratch band with a guest drummer, managed a quick soundcheck, and halfway through the afternoon launched into our first number. Within seconds Mick – our front man and the only real musician in the band - started turning his head and looking back at us with an agonised expression. It wasn’t till the end of the song we saw he’d busted two strings. We soldiered on with our next tune but had to abort the gig halfway through when the park-keeper – in full uniform and shiny peaked cap – wrestled our drummer to the ground, kicking the drums away and screaming “You’re not playing that bloody loud in my park”.

On the 50th birthday of the festival, after Bowie had recently died, the bandstand was given Grade 2 listing as a historical monument and a photo appeared in most newspapers and TV channels. There I was with my violin, somewhere to the rear of a supremely cool-looking Bowie, while Mick sat plucking at his guitar strings."

the Matzos

I played fiddle in The Matzos – a mostly Klezmer band – through the 2000’s. We had loads of fun and did quite well – playing clubs, festivals (including Glastonbury twice) and lots of private weddings, parties etc. It gave me a chance to get the rock and roll out of my system (before it was too late) and I loved it until the schlepping up and down the M25 at the wrong side of midnight finally got to me.